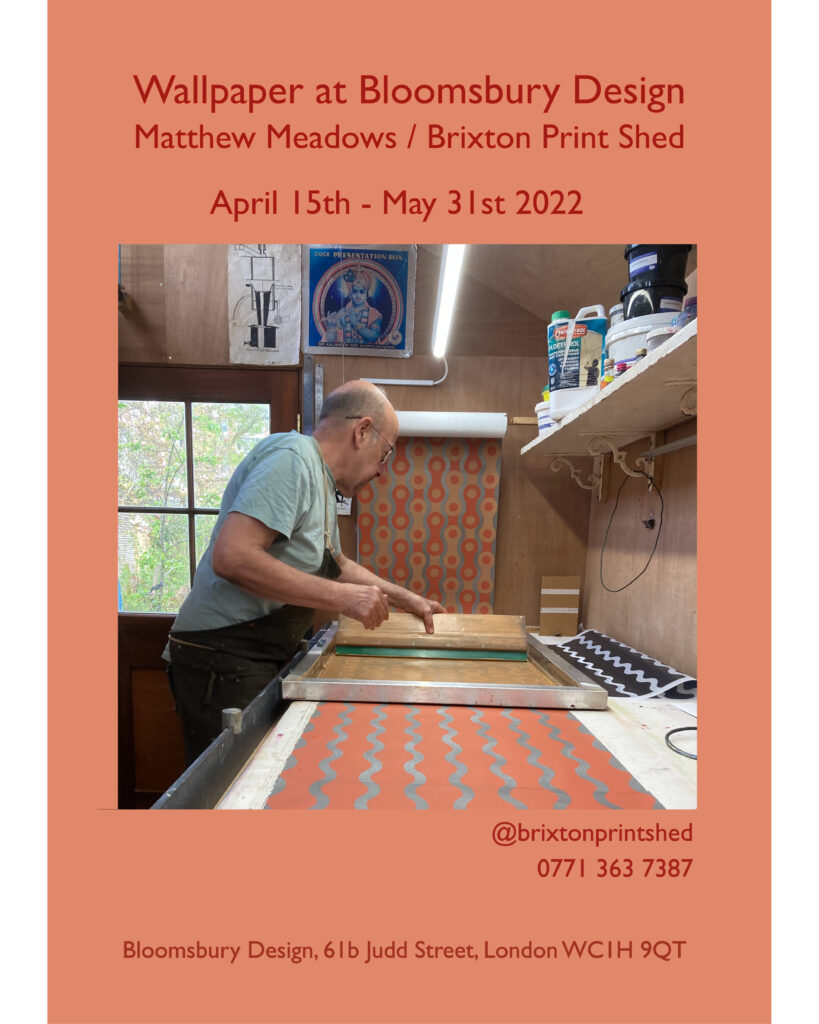

My wallpapers have been on display this month at Bloomsbury Design, 61b Judd Street, London WC1 9QT, UK finishing on May 31st.

Category: Uncategorised

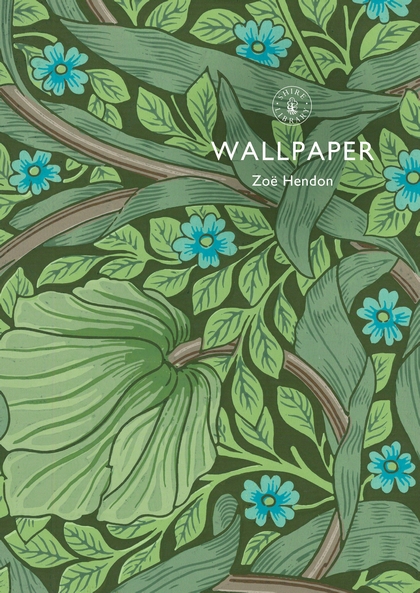

Brixton Print Shed’s Bike Chain featured in recent wallpaper book

Brixton Print Shed’s Bike Chain paper is featured in a recent wallpaper book written by Zoë Hendon, Head of Collections at the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture, London, UK. This usefully compact survey focuses on the development of wallpaper in the UK up to and including contemporary manufacture.It is published by Bloomsbury in their Shire imprint, a series exploring aspects of Britain’s visual heritage.

An xartwalls artist’s wallpaper

The Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam recently staged Machine Spectacle, the largest-ever retrospective of Swiss avant-garde artist Jean Tinguely to be seen in the Netherlands. Tinguely (1925-1991) was a key player in the kinetic art movement of the 1950s; many examples of his noisy and strictly non-functional junkyard machines were working, sadly not the auto-destructive ones for which he is best known. Tinguely, Metger and others ushered in an era of urban art which engaged with social and political issues in public spaces, rather than galleries or museums. Their notion of spectacle challenged the prevailing consumption of art and culture and was to be articulated by Guy Debord in his 1967 publication The Society of The Spectacle.

Graphic work was also on display in the exhibition, some working drawings for machines, also presentations for larger public works, often in collaboration with Tinguely’s partner and fellow artist Niki de Saint Phalle. The final exhibit was a wallpaper, also a collaboration, covering the gallery’s end wall.

In 1968 Tinguely – and a number of other well-known contemporary artists – were approached by Sandro Boccola, who together with partners Heinz Bütler, Rolf Fehlbaum and Erwin Meierhofer founded xartcollection in Zurich that year. The company produced signed multiple editions of industrially manufactured artworks In order to make artists’ work available to a wider audience, and these were partly distributed through a Swiss chain of furniture stores.

In 1971, in collaboration with German company Marburger Tapetenfabrik, xartcollection launched xartwalls, a collection of ‘art’ wallpapers commissioned from 10 artists: Paul Wunderlich, Jean Tinguely, Peter Phillips, Niki de Saint Phalle, Allen Jones, Werner Berges, Getulio Alviani, and Otmar Alt. These papers were screen-printed by Marburg in several colourways and first exhibited in Documenta 5 in 1972. More recently some of these have been exhibited in The Walls Are Talking (Whitworth Gallery, Manchester, UK, 2010) and Faire Le Mur (Musée des Arts Decoratifs, Paris, France, 2016).

Tinguely’s contribution to the xartwalls collection was jointly designed with his partner and fellow artist Niki de Saint Phalle (she also contributed her own distinctive design, one of the better known of Marburg’s artists’ papers); this wallpaper has been digitally reproduced for the exhibition. The original was screen-printed with a choice of 3 background colours: white, pink and silver. The design itself is characteristically surreal, consisting of a half-drop pattern of randomly associating objects scattered across the surface, several referencing Tinguely’s kinetic creations. The xartcollection company went bankrupt in 1973 and in the same year Marburg stopped printing xartwalls papers due to poor sales.

45 years on, an exhibition of Marburg’s wallpapers by all 10 xartwalls artists would be very welcome. Any takers?

Exhibition review: is Palladio having a moment?

Last year the Whitworth Gallery’s wallpaper curator Amy George organized an interesting exhibition of post-war British wallpaper which ran from 29 January to 9 October 2016. This displayed some highlights from the permament collection, focusing on the Palladio range of papers produced for architects from 1955 to 1971.

And to emphasise that these innovative wallpapers really are having a well-deserved moment, MoDA presented a symposium and follow-on display about the Palladio papers in mid-September. Then in December Zoë Hendon – Head of Collections at the Museum of Domestic Design & Architecture – and Christine Woods – ex-curator, wallpaper, the Whitworth Gallery – both gave excellent and complementary presentations about the Palladio papers at the Wallpaper History Society’s AGM; Christine Woods’ talk providing industry information concerning sales, sites and production whilst Zoë Hendon looked at the informal commissioning network of artists and designers centred at the RCA.

Richard and Guy Busby, progressive directors of the Lightbown Aspinall branch of the Wallpaper Manufacturers Ltd (WPM) launched their collections of 100 architects’ papers in 1952. Then following on from the Festival of Britain the Busbys began commissioning another architects’ range – Palladio – to decorate the new public and commercial buildings being built as part of post-war redevelopment; architects wanted larger scale patterns for these big interior spaces, very different from the domestic wallpaper market.

Helped by Roger Nicholson, who with his brother Robert had designed for the Festival of Britain, over 50 artists and designers – including both Nicholsons – were commissioned to produce designs for the first six books of Palladio collections. When Roger Nicholson became head of textiles at the Royal College of Art in 1958, several of his students gained Palladio commissions, notably Audrey Levy, whose designs Maze, Treescape, Universe and Pebble were on display in this exhibition. Garden and Aerial, two patterns by Roger Nicholson were also displayed, illustrating the eclectic range of contemporary styles; Garden, a rustic Edwardian quasi-typeface design, printed in 1950 (probably for John line’s Limited Edition, launched next year at the Festival of Britain) whilst Aerial appeared in the Palladio 5 collection in 1961, a larger scale abstracted aerial perspective evoking Peter Lanyon’s glider paintings of the same period.

The Busby’s decision to commission designs from artists and independent designers via Roger Nicholson’s contacts meant the Palladio range reflected contemporary art and design currents both home and abroad, and it’s worth recalling how this and other factors helped make these collections such a critical success, still recognised today.

The Council of Industrial Design’s recent initiative The Festival Pattern Group, and the exhibition Painting into Textiles at the ICA, London in 1953 (organised by the trade magazine The Ambassador, which promoted fine art as an inspiration to design), reflected fertile exchanges taking place across design disciplines, science and industry, the fine and applied arts, recalling the pre-war generation (Bawden, Marx, Ravillious and others) which had also worked happily across such divides.

In this respect the WPM was playing catch-up with the UK’s textile industry, where artists and designers had already been working with companies like Heal’s, Liberty’s and Whitehead, whilst the more enterprising like Eduardo Paolozzi and Shirley Craven were engaged in lower volume textile production themselves. In addition, the influx of emigré textile designers and manufacturers such as Jacqueline Groag, Tibor Reich, and the Aschers had brought further exposure to Modern Movement ideas, better established on the continent.

The introduction of screen printing after the war had a huge impact on surface design, allowing bigger and larger repeats for both textiles and wallpaper; and with cheaper set-up costs it also allowed for shorter runs, encouraging more speculative and avant-garde designs. Two exhibited papers Rockall by Edward Veevers and Audrey Levy’s Universe (both produced for Palladio 5) demonstrate how effectively designers exploited screen printing’s capacity to reproduce textures and graphic mark-making. Most wall-hung papers in the exhibition were displayed in vertical drops of 3 metres which showed the bigger patterns off well, for example Sunflower, designed by Pat Albeck for the larger scale Palladio collection Magnus 2 in 1961. Its repeat is over a metre long, and a smaller scale version is still produced by Sanderson.

Block and machine printed papers in the ‘Contemporary’ style produced during and after the Festival of Britain were also displayed, including Lucien Day’s Diabolo and Provence, probably the best known and most reproduced pattern of the era.

Several designs won awards, but the Palladio papers were not a commercial success. When WPM was taken over by Reed International in 1966 the collection was transferred from Lightbown Aspinall to Sanderson. Although 5 further Palladio ranges were produced, these were designed by anonymous (and less well-paid) in-house designers and aimed more profitably towards the domestic market.

Matthew Meadows December 2016

My knowledge and appreciation of this exhibition was greatly enhanced (retrospectively) by Christine Woods’ (ex-curator, wallpaper, the Whitworth Gallery) and Zöe Hendon’s (Head of Collections at the Museum of Domestic Design & Architecture). excellent and complementary presentations on the Palladio papers at the Wallpaper History Society’s recent AGM event.